By Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine

Editors of the Folger Shakespeare Library Editions

The play we call Troilus and Cressida was printed in two somewhat different versions in the first quarter of the seventeenth century:

(1) In 1609 appeared The Historie of Troylus and Cresseida, a quarto (Q) that lacks a few short passages of the text with which most modern readers are familiar. Some of these passages are among the most difficult to read in the play, and may have been cut for that reason.

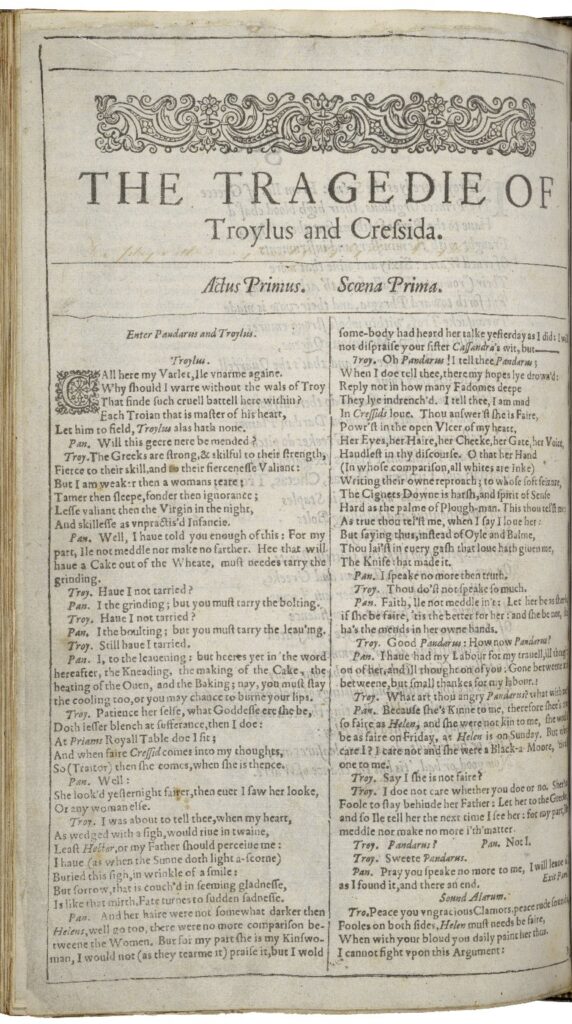

(2) The second version to see print is found in what we now call the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, published in 1623 (F). Titled simply The Tragedie of Troylus and Cressida, F supplies the passages not in Q but lacks, sometimes apparently through error, several lines or pairs of lines that Q preserves. These two versions also differ from each other in their readings in about five hundred places. In a great many of these cases, the difference is limited to the choice of a single word. Variation between Q and F, while a source of ongoing discussion among textual scholars and editors, makes very little difference to most readers.

Explore the 1609 Quarto of Troilus and Cressida in the Folger’s Digital Collections.

(Copy 45 in the Folger Shakespeare Library collection)

Publication of both Q and F was unusually complicated in comparison to that of most of Shakespeare’s plays. Q survives in two different states, each with its own title page, the second state alone containing the prefatory “A neuer writer, to an euer reader. Newes,” printed in this edition in modern spelling. The title page of the first state describes the play as a “Historie” published “As it was acted by the Kings Maiesties seruants at the Globe.” The title page of the second state removes reference to the King’s company of players and their Globe playhouse and describes the play as “The Famous Historie of Troylus and Cresseid. Excellently expressing the beginning of their loues, with the conceited wooing of Pandarus Prince of Licia.” Removal of reference to players and playhouse from the second state’s title page is consistent with the assertions of the second state’s “A neuer writer” that the play was “neuer stal’d with the Stage, neuer clapper-clawd with the palmes of the vulger.” Scholars have differed widely in their interpretations of the contradiction between the first and second states as to whether Troilus and Cressida was ever staged.

Publication of the F version of the play was also complicated. Indeed, the play almost did not become part of the First Folio. A few copies of the book do not contain it, and it was never listed in the Folio’s “Catalogue,” or table of contents. There were two different attempts to include Troilus and Cressida, the second a great deal more successful than the first. Each attempt located the play in a different place in the book, and for each attempt typesetter’s employed a different kind of printer’s copy. Originally, the play was to appear as the fourth of the tragedies, following Coriolanus, Titus Andronicus, and Romeo and Juliet. This intention is clear from the copies of the First Folio that contain a leaf that prints on one side the last page of Romeo and Juliet, numbered page “77,” and on the other side the first page of Troilus and Cressida, unnumbered. On this leaf, the last page of Romeo and Juliet is crossed off in pen and ink to indicate that the leaf is to be canceled, rather than bound up with a finished book—an indication that was not always noticed or observed, as the survival of copies of the leaf demonstrates. Also printed at the same time was the leaf containing the second and third pages of F Troilus, as is indicated by their being numbered pages “79” and “80.” These are the only pages of the F version to contain page numbers, although all the rest of the Folio plays are printed on pages that are numbered throughout. The text of Troilus and Cressida found on these three pages is almost identical to that found in Q, except for some printers errors and the correction of a few of the most obvious errors in Q, such as the omission of an entrance for Pandarus at 1.2.40 SD.

Before any more of Troilus could be printed, there was a change of plan and a relocation of the play within the book. Now Troilus and Cressida was placed between Henry VIII, the last of the history plays that constitute the middle section of the book, and Coriolanus, the first play in the concluding tragedies section. This is where Troilus and Cressida appears in the great majority of the extant copies of the First Folio. In these copies, in place of the canceled leaf on which Troilus’s first page was initially printed, there is a leaf that contains on one side “The Prologue” (which had not been printed in the first attempt) and on the other side the first page of the play. This second printing of this page was evidently set into type directly from its first printing, because the second printing contains errors introduced during the first. Following this reset first page come pages “79” and “80”; their appearance indicates that they were saved from the interrupted initial attempt to print the play. The rest of Troilus and Cressida then follows, printed on twenty-five unnumbered pages.

These twenty-five pages were evidently set from a different kind of printer’s copy than that used in the first attempt. During that attempt, the typesetter seems to have worked simply to reproduce word for word the text of the play that appears in Q; if there were any pen-and-ink changes made to the typesetter’s copy of Q, they were very few, and they could have been made without anyone’s consulting a manuscript source. But the twenty-five pages printed in the second attempt contain so many more departures from and additions to the Q text that the printer must have had recourse to a manuscript version of the play in addition to Q. It would have been from this manuscript that the printer would also have acquired the Prologue, which is unique to F.

Precisely how this manuscript was used in the printing house has been the subject of debate. Some, including the present editors, favor the view that the last twenty-five pages of F were printed directly from a copy of Q that had been annotated with reference to a manuscript, perhaps with some of the additional short passages having been copied onto slips of paper that were interleaved among the pages of the Q copy. This view is based not only on the many errors shared by Q and F, but also on the reappearance of typographical peculiarities from Q in F. For example, of the fifty-five occurrences of the word Troy in the play’s dialogue, it is printed in roman type forty-seven times in the same places in both Q and F; in the five places it is printed in italic in Q, it is also in italic in F; and there are only three places where the word is printed in roman in Q but in italic in F. It would seem, then, that F was set directly from printed copy, just as were a number of other plays—A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, and Henry IV, Part 1, to name only three. Despite such evidence, some scholars have raised an objection to this view. Citing the appearance of errors in F in places where Q is self-evidently correct, they argue that it is impossible that an annotator of Q would have deliberately replaced these Q readings with F’s errors. Consider the following useful example; the quotation is from Q, with the variants from F added in pointed brackets:

Vlis. Shee will sing any man at first sight.

Ther. And any man may sing ⟨finde⟩ her, if hee can take her Cliff ⟨life⟩, she’s noted.

(5.2.11–14)

Admittedly, no intelligent annotator would have substituted the bracketed F readings for Q’s words. However, it is entirely possible that the errors in F originate with the typesetter, not the annotator: study of typesetters’ performance in reprinting quartos of other plays for the Folio shows that they were capable of straying from their perfectly clear printed copy in ways not unlike what we find in the passage quoted. Thus there is no need to qualify or abandon the inference that F was set from an annotated and perhaps interleaved copy of Q.

Usually, twentieth-century editors of Shakespeare determined their preferences regarding versions of a play according to their theories about the origins of the early printed texts. In the case of Troilus and Cressida, however, there emerged no consensus among editors about the kinds of manuscript lying behind Q or behind the annotations incorporated into the printing of F. For much of the twentieth century, it was argued that the manuscript used to annotate Q copy for F was Shakespeare’s own draft of the play; some repetitions in F were interpreted as arising from his incompletely deleted first shots that had been replaced by second thoughts (see the Textual Notes at 4.5.110 and 5.3.123). In contrast, Q was thought to be based on a scribal transcript that preserved some of Shakespeare’s revisions to the earlier version found in F. There followed an attempt to turn this account upside down and to establish that Q, rather than F, represented Shakespeare’s own draft and that the manuscript used to annotate Q copy for F was Shakespeare’s revision of his play. More recently, another editor has suggested that Q may derive from a transcript of the play, perhaps by Shakespeare, that contains some of his revisions, further speculating that F may derive from a different manuscript of Shakespeare’s that contains other revisions.

While scholarly opinions about the manuscript sources of Q and F are very much at odds, we can be confident that the manuscript used to annotate Q copy for F came from the playhouse. Good evidence for this conclusion is the number of stage directions calling for sounds (sound calls) that are added to the F text. These can be found, for example, at 1.3.0, 1.3.216, 3.1.0, 3.3.0, 4.4.149, and 5.4.0. In several non-Shakespearean plays that survive in playhouse manuscripts, sound calls are one kind of stage direction that we find repeatedly added in the margin in the hands of theatrical personnel. Unfortunately, identification of the theatrical provenance of the manuscript used to annotate the copy of Q employed by the F printers does nothing to determine whether Q or F is the better text on which to base an edition. Among surviving theatrical manuscripts, we find both authorial and scribal copies of widely varying quality.

Our decision to select Q as the basis for this edition is based on our evaluation of the quality of the readings in the two versions, rather than on any of the conflicting accounts of the origins of Q and F. There are problems with both texts. Q prints many errors, a number of them apparently the result of careless copying or typesetting. One particularly bad passage occurs in 5.1.59–62, where Q mistakenly prints “faced” (corrected in F to “forced”), “hers” (corrected in F to “hee is”), “day” (corrected in F to “Dogge”), and “Moyle” (corrected in F to “Mule”). Another batch of Q errors appear to be examples of what is called contextual variation. This error occurs when the eye and attention of a scribe or compositor strays from the word to be copied toward another word in the immediate context, and the scribe or compositor erroneously copies or sets the other word. The transcript or the printed version then varies from the original under the influence of context. One striking example of such an error occurs at 5.1.15, where in Q Thersites orders Patroclus to “be silent, box,” and F corrects Q’s nonsensical “box” to the intelligible “boy.” Q’s choice of word occurs two lines above in the phrase “Surgeons box,” and it is to be suspected that some agent in the transmission of Q from Shakespeare into print, whether a scribe or a compositor, allowed his eye to wander from “boy” to “box,” and repeated “box” in error. Although there is no good evidence that deliberate changes were introduced into the text that Q preserves, Q shows so many careless errors that we, as editors, would prefer not to have to rely on Q.

But we feel that we must; for although F displays fewer careless errors than Q, F may also contain what can be interpreted as calculated but unnecessary attempts to improve and clarify the play’s language. For example, in the following exchange F’s intervention seems primarily to endow Thersites’ speech with a touch of formality:

ACHILLES Why, but he is not in this tune, is he?

THERSITES No, but ⟨he’s⟩ out of tune thus.

(3.3.314–15)

As another example, F’s addition to 2.3.66–68 may be erroneous in its redundancy and ambiguity: “Agamemnon is a fool to offer to command Achilles, Achilles is a fool to be commanded ⟨of Agamemnon,⟩ Thersites is a fool to serve such a fool. . . .” It is obvious from the first clause who Achilles’ would-be commander is. Furthermore, by introducing “of Agamemnon” into the second clause, F makes the reference “such a fool” in the third clause harder to read than it was in Q. In F, but not in Q, the phrase could refer either to Achilles, whom Thersites does serve and to whom the phrase clearly refers in Q, or to Agamemnon. However, it is to be acknowledged that this suspicion of F’s reading holds the informal conversation of the dialogue accountable to strict stylistic and grammatical standards.

F’s most striking error occurs at 5.1.21–24. In Q, Thersites concludes the curse he calls down on Patroclus of “the rotten diseases of the south” by naming “could palsies, rawe eies, durt rotten liuers, whissing lungs, bladders full of impostume, sciaticas, lime-kills ith’ palme, incurable bone-ach, and the riueled fee simple of the tetter . . .”; F deletes most of the list, reducing it to “palsies, and the like.” Clearly, some agent in the transmission of F had no qualms about discarding Shakespeare’s language. It is therefore just possible that the rest of F’s verbal substitutions and additions—those that are not corrections of obvious Q errors—also proceed from such an agent’s attempt to improve, sophisticate, or otherwise change Shakespeare. There is nothing so remarkable about the F-only readings that we feel compelled to invoke Shakespeare as the only conceivable source of them. The possibility that F is a sophisticated version not only may undercut many editors’ confidence that F preserves Shakespeare’s own revisions but also leads us, as editors, to prefer Q, which does not arouse the same kind of suspicions about wrong-headed attempts to enhance the text.

This edition therefore offers its readers the Q version of Troilus and Cressida and is based directly upon that printing.1 But our text offers an edition of Q, because it prints such F readings and such later editorial emendations as are, in the editors’ judgments, necessary to repair what may be errors and deficiencies in Q. At the same time, this edition provides readers access to the F version, in spite of our suspicions of the F text, by offering the lines and part-lines and many of the words that are to be found only in F, marking them as coming from F (see below). We want to allow readers, to the full extent possible within the bounds of a single edition, to arrive at their own judgments about the relative quality of Q and F.

Occasionally, too, F readings are substituted in our text for Q words. This substitution occurs under the following circumstances:

(1) Whenever a word in Q is unintelligible (i.e., is not a word) or is incorrect according to the standards of that time for acceptable grammar, rhetoric, idiom, or usage, and F provides an intelligible and acceptable word (recognizing that our understanding of what was acceptable in Shakespeare’s time is to some extent inevitably based on reading others’ editions of Troilus and Cressida, but also drawing on reading of much other writing from the period).

(2) Whenever Q can reasonably be suspected to have committed its characteristic error of contextual variation, even though the Q reading is intelligible. For example, at 4.5.70, Q reads “ticklish reader,” a perfectly intelligible reading, while F reads “tickling reader,” which is equally acceptable. However, we choose to read with F because in the next line both texts read “sluttish,” a word whose ending may well have influenced the Q reading in the line above.

In order to enable its readers to tell the difference between the Q and F versions, the present edition uses a variety of signals:

(1) All the words in this edition that are printed only in the F version but not in Q appear in pointed brackets (⟨⟩).

(2) All lines that are found only in Q and not in F are printed in square brackets ([ ]).

(3) Sometimes neither Q nor F seems to offer a satisfactory reading, and it is necessary to use a word different from what is offered by either. Such words (called “emendations” by editors) are placed within superior half-brackets (⌜ ⌝). We employ these brackets because we want our readers to be immediately aware when we have intervened. (Only when we correct an obvious typographical error in Q or F does the change not get marked.) Whenever we change the wording of Q or F, or alter their punctuation so that meaning changes, we list the change in the textual notes, even if all we have done is fix an obvious error. By observing these signals and by referring to the textual notes, a reader can use this edition to read the play as it was printed in Q, or as it was printed in F, or as it has been presented in the modern editorial tradition that usually has combined Q and F.

For the convenience of the reader, we have modernized the punctuation and the spelling of Q and F. Sometimes we go so far as to modernize certain old forms of words; for example, usually when a means “he,” we change it to he; we change mo to more, and ye to you. But it is not our practice in editing any of the plays to modernize words that sound distinctly different from modern forms. For example, when the early printed texts read sith or apricocks or porpentine, we have not modernized to since, apricots, porcupine. When the forms an, and, or and if appear instead of the modern form if, we have reduced and to an but have not changed any of these forms to their modern equivalent, if. We also modernize and, where necessary, correct passages in foreign languages, unless an error in the early printed text can be reasonably explained as a joke.

We regularize spellings of a number of the proper names, as is the usual practice in editions of the play. For example, in Q we find the following spellings of character names: Deiphobus and Diephobus, Helen and Hellen, Calchas and Calcas, Cressida and Cresseida. In this edition, we use only Deiphobus, Helen, Calchas, and Cressida. We also expand the often severely abbreviated forms of names used as speech headings in early printed texts into the full names of the characters. In addition, we regularize the speakers’ names in speech headings, using only a single designation for each character, even though the early printed texts sometimes use a variety of designations. Variations in the speech headings of the early printed texts are recorded in the textual notes.

This edition differs from many earlier ones in its efforts to aid the reader in imagining the play as a performance rather than as a series of actual events. Thus stage directions are written with reference to the stage. For example, when, near the end of the play, Pandarus approaches Troilus with, according to the dialogue, “a letter from yond poor girl” Cressida, Pandarus would not bring onto the stage an actual letter. Instead, he would carry only a stage-prop piece of paper, which Troilus then acts as if he were reading and finally tears up. Thus we print “Enter Pandarus, with a paper,” not “a letter,” thereby choosing the direction that refers more to the staging than to the story.

Whenever it is reasonably certain, in our view, that a speech is accompanied by a particular action, we provide a stage direction describing the action, setting the added direction in brackets to signal that it is not found in Q or F. (Exceptions to this rule occur when the action is so obvious that to add a stage direction would insult the reader.) Stage directions for the entrance of a character in mid-scene are, with rare exceptions, placed so that they immediately precede the character’s participation in the scene, even though these entrances may appear somewhat earlier in the early printed texts. Whenever we move a stage direction, we record this change in the textual notes. Latin stage directions (e.g., Exeunt) are translated into English (e.g., They exit).

In the present edition, as well, we mark with a dash any change of address within a speech, unless a stage direction intervenes. When the -ed ending of a word is to be pronounced, we mark it with an accent. Like editors for the past two centuries, we display metrically linked lines in the following way:

In all swift haste.

TROILUS Come, go we then together.

(1.1.119–20)

However, when there are a number of short verse-lines that can be linked in more than one way, we do not, with rare exceptions, indent any of them.