By Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine

Editors of the Folger Shakespeare Library Editions

The play we call King Lear was printed in two different versions in the first quarter of the seventeenth century.

In 1608 appeared M. William Shak-speare: His True Chronicle Historie of the life and death of King Lear and his three Daughters. With the vnfortunate life of Edgar, sonne and heire to the Earle of Gloster, and his sullen and assumed humor of Tom of Bedlam. This printing was a quarto or pocket-size book known today as “Q1.” It is remarkable among early printed Shakespeare plays for its hundreds of lines of verse that are either erroneously divided or set as prose; in addition, some of its prose is set as verse. As Q1 was going through the press, it was extensively corrected; thus different copies of its pages contain different readings. Sometimes the correction appears to be competent; at other times, however, it is better called “miscorrection.” (In 1619 appeared a second quarto printing of the play [“Q2”]. It was, for the most part, simply a reprint of Q1, but it contained many corrections [as well as new errors] and changes, especially in the lining of verse in the last scene or so of Act 4 and in Act 5. This second printing had exactly the same title as Q1, and it even retained on its title page the 1608 date of Q1; the true date of Q2’s printing [1619] was not discovered until early in the twentieth century.)

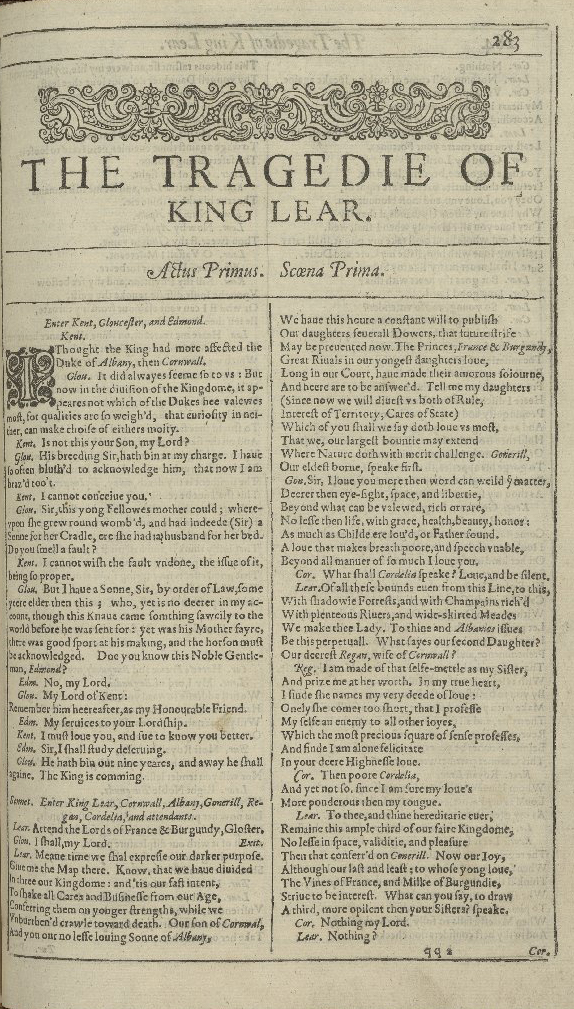

The second version to see print is found in the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, published in 1623 (“F”). Entitled simply The Tragedie of King Lear, F contains over 100 lines that are not in Q1; at the same time F lacks about 300 lines (including a whole scene, 4.3) that are present in Q1. Many of the lines unique to Q1 or to F cluster together in quite extensive passages. The Q1 and F versions also differ from each other in their readings of over 800 words. In spite of the wide differences between the quarto and Folio printings, there is, nevertheless, such close agreement in punctuation between Q2 and F on some pages that the suspicion arises that the F typesetters may have referred to Q2 even if their copy was a manuscript. Thus when F agrees with Q2 against Q1, editors sometimes suspect that F may have been led into error by Q2 (see, for example, in the textual notes 1.4.32, 141; 2.1.141; 2.2.165; 4.2.74, 96; 4.6.299; 4.7.68; 5.3.186). In other cases, however, F agrees with Q2 in the correction of obvious (or nearly obvious) errors in Q1 (see, for example, in the textual notes 1.1.163; 1.4.327; 1.5.8; 2.1.13SD, 63; 2.2.98, 152, 163, 171; 2.4.121; 186, 246; 3.3.3; 3.7.90; 4.1.10; 4.2.18; 4.4.30; 4.5.8; 4.6.49, 53, 85, 100, 127, 286; 5.1.63; 5.2.5SD; 5.3.30SD, 365, 370).

Explore the First Quarto of King Lear (1608) in the Folger’s Digital Collections.

(Copy 9 in the Folger Shakespeare Library collection.)

Since early in the eighteenth century, editors have combined Q1 and F to produce what is termed a “conflated text.” But it is impossible in any edition to combine the whole of the two versions, because they often provide alternative readings that are mutually exclusive; for example, when Q1 has the earl of Gloucester in his first speech refer to Lear’s planned “division of the kingdoms,” the Folio prints the singular “kingdom.” In such cases (and there are a great many such cases), editors must choose whether to be guided by Q1 or by F in selecting what to print.

Twentieth-century editors of Shakespeare made the decision about which version of King Lear to prefer according to their theories about the origins of the early printed texts. For the greater part of the century, editors preferred F to Q1 in the belief that the Q1 text originated either in a shorthand transcription of a performance or in a reconstruction of the play by actors who depended on their memories of their parts. On the other hand, the F text was believed to have come down to us without the intervention of shorthand or memorial reconstruction. In the past few decades, however, Q1 has found more favor with some editors according to a theory that it was printed directly from Shakespeare’s own manuscript and that F was set into type from a version of the play that had been rehandled by another dramatist after Shakespeare’s retirement from the theater. This second theory is today in competition with yet a third theory that holds that Q1 and F are distinct, independent Shakespearean versions of the play that ought never to be combined with each other in an edition. Those who hold this third theory think that Q1 was printed from Shakespeare’s own manuscript, but they also think that the F text is the product of a revision of the play by Shakespeare after the printing of Q1. Nevertheless, as scholars reexamine all such narratives about the origins of the printed texts, we discover that the evidence upon which they are based is questionable, and we become more skeptical about ever identifying with any certainty how the play assumed the forms in which it was printed.

The present edition is based upon a fresh examination of the early printed texts rather than upon any modern edition.1 It offers its readers the Folio printing of King Lear.2 But it offers an edition of the Folio because it prints such Q1 readings and such later editorial emendations as are, in the editors’ judgments, necessary to repair what may be errors and deficiencies in the Folio. Furthermore, the present edition also offers its readers all the passages and a number of the words that are to be found only in Q1 (and not in F), marking them as such (see below).

Q1 words are added when their omission seems to leave a gap in our text. For example, in the first scene of the play, a speech of Cordelia’s concludes in F with the line “Sure I shall never marry like my sisters”—without specifying the respect in which her marriage will differ from theirs. Q1 alone provides the required specification with an additional half-line, “To love my father all,” and we include Q1’s half-line in our text. (For similar additions, see 1.1.49, 75, 175, 246, 335; 1.2.140–41; 1.3.29; 1.4.195, 267–68, 321; 2.2.29; 3.2.85; 3.4.51, 52, 122, 143; 4.1.48; 4.5.43; 4.6.299; 4.7.28, 67; 5.1.20; 5.3.54. In a number of these cases the Q1 word or words are added to fill out short [and metrically deficient] lines in F.) We also add an oath from Q1 (“Fut,” 1.2.138) that may have been removed from the F text through censorship. However, when F lacks Q1 words that appear to add nothing of significance, we do not add these words to our text. For example, Q1 adds the word “attire” to the end of Lear’s statement to Edgar, “I do not like the fashion of your garments. You will say they are Persian” (3.6.83–85). Here the Q1 word “attire” seems a mere repetition of the earlier “garments.” (Compare, among many instances, Q1 additions not included in our text—words that are sometimes needless, sometimes superfluous—listed in the textual notes at 1.1.60; 2.4.266; 3.6.83; 3.7.66, 68; 4.6.298.)

Sometimes Q1 readings are substituted for F words when a word in F is unintelligible (i.e., not a word) or is incorrect according to the standards of that time for acceptable grammar, rhetoric, idiom, or usage, and Q1 provides an intelligible and acceptable word. Examples of such substitutions are Q1’s “fathers” (modernized to “father’s”) for F’s “Farhers” (1.2.18), Q1’s “your” for F’s “yout” (2.1.122), Q1’s “possesses” for F’s “professes” (1.1.82), or Q1’s “panting” for F’s “painting” when Oswald is referred to as “half breathless, ⟨panting⟩” (2.4.36). (Compare substitutions from Q1 at 1.1.5, 72, 176, 259; 1.4.1, 51, 164, 182, 203; 2.1.2, 61, 80, 92, 101–2, 144; 2.2.0SD, 23, 82, 83, 131, 141, 166, 187; 2.3.4, 18, 19; 2.4.8, 12, 39, 65, 82, 144, 146, 212; 3.2.3; 3.4.12, 51, 56, 57, 97, 123; 3.5.26; 3.6.73; 4.1.65; 4.2.91; 4.4.3, 12SP, 20; 4.6.22, 77, 102, 180, 300; 4.7.0SP, 15SP; 5.1.52, 55; 5.3.82SP, 99, 101, 118, 160, 163, 177, 308.) We recognize that our understanding of what was acceptable in Shakespeare’s time is to some extent inevitably based upon reading others’ editions of King Lear, but it is also based on reading other writing from the period and on historical dictionaries and studies of Shakespeare’s grammar.

Finally, we print a word from Q1 rather than from F when a word in F seems at odds with the story that the play tells and Q1 supplies a word that coheres with the story. For example, when Lear enters at the beginning of 2.4 he wonders, in F, why Cornwall and Regan did “not send back my Messengers.” But, as far as we know, Lear has sent only a single messenger (Kent) to Cornwall and Regan. Therefore, like most other editors, we print Q1’s “messenger” for F’s “Messengers.” (Compare 1.1.214 and 5.3.193.) Because we rarely substitute Q1 words for F’s, our edition is closer to F than are most other editions of the play available today.

In order to enable its readers to tell the difference between the F and Q1 versions, the present edition uses a variety of signals:

(1) All the words in this edition that are printed only in the First Quarto but not in the Folio appear in pointed brackets (⟨ ⟩).

(2) All full lines that are found only in the Folio and not in the First Quarto are printed in brackets ([ ]).

(3) Sometimes neither the Folio nor the First Quarto seems to offer a satisfactory reading, and it is necessary to print a word different from what is offered by either. Such words (called “emendations” by editors) are printed within half-brackets (⌜ ⌝).

In this edition, whenever we change the wording of the Folio or add anything to its stage directions, we mark the change. We want our readers to be immediately aware when we have intervened. (Only when we correct an obvious typographical error in the First Quarto or Folio does the change not get marked in our text.) Whenever we change the Folio or Quarto’s wording or change their punctuation so that meaning is changed, we list the change in the textual notes. Those who wish to find the Quarto’s alternatives to the Folio’s readings will be able to find these also in the textual notes.

For the convenience of the reader, we have modernized the punctuation and the spelling of both the Folio and the First Quarto. Thus, for example, our text supplies the modern standard spelling “father’s” for the Quarto’s spelling “fathers” (quoted above). Sometimes we go so far as to modernize certain old forms of words; for example, when a means “he,” we change it to he; we change mo to more and ye to you. But it is not our practice in editing any of the plays to modernize forms of words that sound distinctly different from modern forms. For example, when the early printed texts read sith or apricocks or porpentine, we have not modernized to since, apricots, porcupine. When the forms an, and, or and if appear instead of the modern form if, we have reduced and to an but have not changed any of these forms to their modern equivalent, if. We also modernize and, where necessary, correct passages in foreign languages, unless an error in the early printed text can be reasonably explained as a joke.

We correct or regularize a number of the proper names, as is the usual practice in editions of the play. For example, the Folio’s spellings “Gloster” and “Burgundie” are changed to the familiar “Gloucester” and “Burgundy”; and there are a number of other comparable adjustments in the names.

This edition differs from many earlier ones in its efforts to aid the reader in imagining the play as a performance rather than as a series of historical events. Thus stage directions are written with reference to the stage. For example, in 1.2 Edmund is represented in the dialogue and in the fiction of the play as putting a letter in his pocket. On the stage this letter would, however, be represented by a piece of paper. Thus the present edition reads “He puts a paper in his pocket” rather than “a letter.”

Whenever it is reasonably certain, in our view, that a speech is accompanied by a particular action, we provide a stage direction describing the action. (Occasional exceptions to this rule occur when the action is so obvious that to add a stage direction would insult the reader.) Stage directions for the entrance of characters in mid-scene are, with rare exceptions, placed so that they immediately precede the characters’ participation in the scene, even though these entrances may appear somewhat earlier in the early printed texts. Whenever we move a stage direction, we record this change in the textual notes. Latin stage directions (e.g., Exeunt) are translated into English (e.g., They exit).

We expand the often severely abbreviated forms of names used as speech headings in early printed texts into the full names of the characters. We also regularize the speakers’ names in speech headings, using only a single designation for each character, even though the early printed texts sometimes use a variety of designations. Variations in the speech headings of the early printed texts are recorded in the textual notes.

In the present edition, as well, we mark with a dash any change of address within a speech, unless a stage direction intervenes. When the -ed ending of a word is to be pronounced, we mark it with an accent.

Like editors for the last two centuries, we display metrically linked lines in the following way:

Mak’st thou this shame thy pastime?

KENT No, my lord.

However, when there are a number of short verse lines that can be linked in more than one way, we do not, with rare exceptions, indent any of them.

- We have also consulted a computerized text of the First Folio provided by the Text Archive of the Oxford University Computing Centre, to which we are grateful. Also of great value was Michael Warren’s The Complete King Lear (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

- We choose F not because we believe that it stands in closer relation to Shakespeare than Q1 (we do not think it possible to establish which of Q1 or F is closer to the historical figure Shakespeare) but because F is a “better” text than Q1 in that it requires an editor to make fewer changes to its line division and wording than an editor must make to Q1.