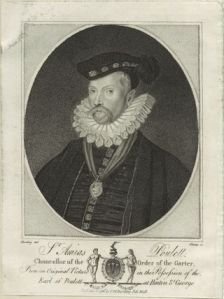

- Amias Paulet

- Louis Butelli as Amias Paulet.

Hello from your friend Louis Butelli. We’re having a blast running Schiller’s Mary Stuart at Folger Theatre. The audiences have been fantastic, the press has been enormously positive, and we hope you’ll join us before we close this production on March 8.

While our story revolves around two historical Queens, Elizabeth I and Mary of Scotland, the play’s centerpiece is a meeting between the two women at Fotheringay Castle…a meeting that is entirely fictional. This explosive scene, which begins directly after our intermission, never actually happened.

Poetic licence. Photo by Teresa Wood.

This got me thinking about the ways in which our playwright Friedrich Schiller and our adapter/translator Peter Oswald have blended actual people and events with fictional people and events to create a work which is, for want of a better phrase, more than the sum of its parts.

Historically, all of the contact between Elizabeth and Mary was in the form of letters. One imagines that such a play might be, shall we say, less-than-dramatic. Far more gratifying is to put the two women in the same place at the same time and see what happens.

Louis Butelli as Amias Paulet. Photo by Teresa Wood.

Meanwhile, it turns out that my role, Mary’s jailer Sir Amias Paulet, is in fact based on an actual man. Here’s a brief history, taken from Luminarium.org – an online anthology of English literature.

Sir Amyas Paulet was born around 1536 to Sir Hugh Paulet, Governor of Jersey, and his first wife. He became his father’s lieutenant at age 23 and, with strong Puritan values, distinguished himself by suppressing all of the local Catholics.

On his father’s death, he assumed the Governorship, but soon delegated it to his brother in order to accept a knighthood and travel to France to serve as England’s ambassador. His tenure in France was serviceable, if unremarkable, and he was recalled.

Amias Paulet.

In 1585, he was selected to become Mary’s jailer, a dubious honor at best and one that came at no small personal cost:

Upon Mary’s execution in 1587, at which Paulet was present, he was released from his duties and was appointed Chancellor of the Order of the Garter, an office he held until his death just a year later.

In sniffing around the internet for traces of Sir Paulet, I came upon a book of his letters: “The Letter-Books of Sir Amias Poulet, Keeper of Mary Queen of Scots,” John Morris, Editor, Burns & Oates, 1874. Like many noble men and women, the two Queens included, Paulet was a copious letter writer.

Nancy Robinette as Hanna Kennedy and Louis Butelli as Amias Paulet. Photo by Teresa Wood.

What fascinates me most is hearing the man “speak” for himself. In Mary Stuart, Sir Amias is adapted and folded in to a larger narrative in which he plays a fairly ancillary role. Still, nobody is a “bit player” in their own life and reading the seriousness with which he composed his correspondence opened a small window into the life of a man whom we scarcely meet in the play.

That said, following along the text we’re performing, Richard Clifford’s excellent direction, and some of the choices I’ve tried to make as an actor, our Sir Amias Paulet is actually fairly close to the actual Paulet, or at least to the voice of the man as it emerges in one of his letters to Queen Elizabeth.

I’ll close this entry by quoting him, in his own words, as he describes to Queen Elizabeth a conversation he had with Queen Mary:

And now, Madame,” quoth I, “it may please you to give me leave to say something unto you concerning myself, and do trust that being sent hither in such sort and for such purpose as hath appeared unto you, it will not mislike you, and would stand best with the discharge of my duty in many respects, if at my first entrance unto this place, I declare unto you in plain terms what I desire to find at your hands, and at the hands of all those belonging unto you, and what you may expect from me, because plain dealing is always best.

It is a thing that I love well,” quoth she, and promised to deal as plainly with me. I swore that I was bound by duty of allegiance to serve your Majesty truly and faithfully, and would not fail to employ all my endeavors to acquit myself of that duty, neither would be diverted from it for hope of gain, for fear of loss, or for any other respect whatsoever.

Your Highness’ commandment and service being first observed, I did assure her that your pleasure was that I should do her all the good offices, and show her all the courtesy that might seem convenient, wherein there should be no fault on my part.

Nancy Robinette, Kate Eastwood Norris, and Louis Butelli. Photo by Teresa Wood.

The cast and crew of Mary Stuart. Photo by Teresa Wood.

He is proper, he is thorough, he is loyal and, if one looks a little bit beneath what he’s written – it is a letter to the Queen of England, after all, which requires a fair amount of delicacy – he is careful to demonstrate that he is less prepared to be cruel to Mary. Or rather, he is prepared to be as courteous as the situation can possibly allow him to be.

Come on down to Folger Theatre and meet Sir Amias Paulet, and a vibrant cast of characters in Mary Stuart.

Until next time…

Stay connected

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Comments

Wonderful play! Saw it on Feb. 17. Loved how Sir Amias challenged Lord Burleigh, by a few words and gesture, to allow Hanna to accompany her mistress to the end. More than a convenient courtesy, it was brave and merciful. Very moving.

Alice Moore — February 21, 2015

Wow, thank you, Alice! Thanks for coming out to see us, thanks for kind words and thanks for reading. You’ve put a big smile on my face.

Louis Butelli — February 22, 2015