Hello again! Your pal Louis Butelli here with the second in a series of blog posts in advance of Folger Theatre’s upcoming production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

Recently, I wrote about a recent debate on Twitter concerning whether or not the plays of William Shakespeare are “relatable,” and whether or not it matters (read the article here). That got me thinking about Julius Caesar. I wondered what, if anything, about the play is relevant right now.

As I type this, the news media are presenting two major stories: civil unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, and the activities of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. Images of civilians clashing with armed, militarized forces flash across screens worldwide, while the rest of us watch anxiously, wondering how these events will play out. Analysis is fast and furious, passionate and partisan. Social media is ablaze with debate and feelings of impotence; our hands are seemingly tied. Apart from watching, there doesn’t seem to be much we can actually do to help.

Of course, the events mentioned above are radically different in context. Still, there are parallels between them: both represent the spontaneous, escalating reaction of a large group of people acting in unison.

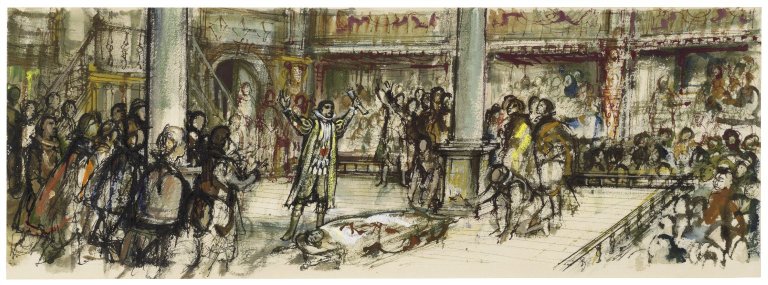

For some, when one mentions the play Julius Caesar, the first thing to pop into one’s head is the quote, “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears,” which is the opening salvo of MarK Antony’s famous funeral oration. In a brilliant piece of rhetoric, Antony addresses an angry crowd, and masterfully re-directs them, inciting them to violence.

What is it that makes human beings react in concert to an event? What are the social and cultural ingredients that cause a crowd to coalesce? At what point does a peaceful gathering turn violent? All of these are questions that Julius Caesar, a play written some 415 years ago, inspires us to ask today.

*Please note: although this blog will not take a political stance on either of the news items mentioned above, the author has many strong feelings, and is happy to discuss them with you at great length elsewhere, starting here.

History is full of examples of violent clashes of this sort.

From the Salem Witch trials and the Boston Massacre to Selma, Alabama and Crown Heights, New York, the United States has also seen its fair share of civil unrest. Relevant to our interests here is the Astor Place Riot, about which our friends at Wikipedia say:

“The Astor Place Riot occurred on May 10, 1849 at the now-demolished Astor Opera House in Manhattan, New York City and left at least 25 dead and more than 120 injured. It was the deadliest to that date of a number of civic disturbances in New York City which generally pitted immigrants and nativists against each other, or together against the upper classes who controlled the city’s police and the state militia.

The riot marked the first time a state militia had been called out and had shot into a crowd of citizens, and it led to the creation of the first police force armed with deadly weapons, yet its genesis was a dispute between Edwin Forrest, one of the best-known American actors of that time, and William Charles Macready, a similarly notable English actor, which largely revolved around which of them was better than the other at acting the major roles of Shakespeare.”

Here, as in so many instances of civil unrest throughout the ages, one tends to latch onto the inciting incident (in this case, a Shakespearean dispute) rather than the underlying root cause (a clash between social castes). One can almost hear Julius Caesar‘s Cassius speaking: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in ourselves that we are underlings.”

While humans have been familiar with events such as these from the beginning, it was not until the late 19th century, when the nascent field of psychology arose, that we began to consider the “why” of the crowd.

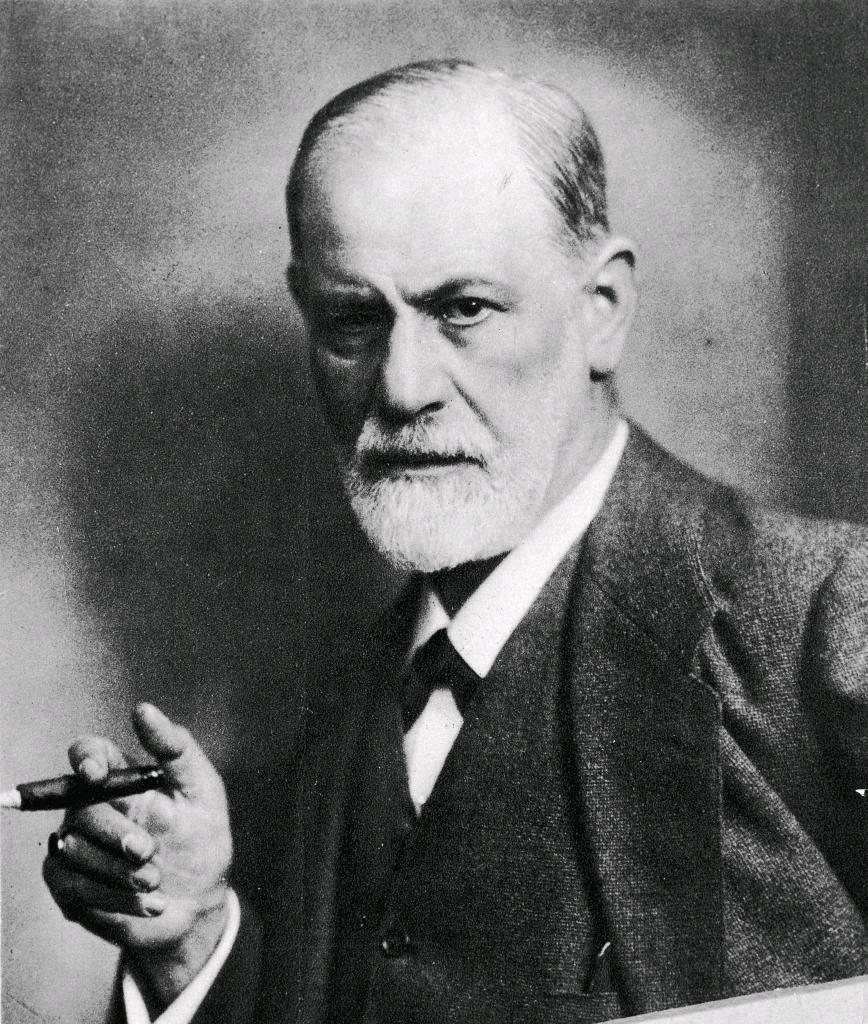

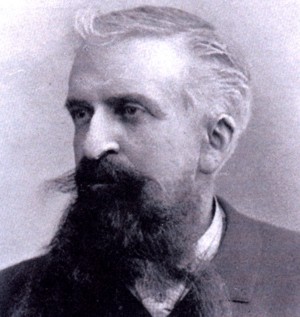

Two names loom large: French anthropologist and social psychologist Gustave Le Bon (1841-1931), and Austrian neurologist and father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud (1856-1939).

While these two were of a social strata afforded the luxury of contemplating the semantics of such things, and while their conclusions may feel a little bit dated to some, their observations are certainly worth repeating, albeit in bite-sized form.

In his analysis of Freud’s seminal work on the subject, “Group Psychology and the History of the Crowd,” Daniel Pick (History Workshop Journal, issue 40, 1985) says:

“I am suggesting that Freud…brings the meanings of ‘I’ and ‘we’ into question. How do the cacophony of voices, figures, objects – the whole jostling crowd – come together into the mysterious and always troubling notion of the self? To what extent can history or politics provide an adequate account of the ‘making’ of the self?”

This difference between “I” and “we” is both crucial and hard to pin down. We see the oddness of differentiating between the two in language itself.

It is fascinating that Freud conceived of the group as something very different from a collection of “I’s.” Rather, it becomes something unique, something with its own set of rules, something with a mind of its own. This notion is familiar to us from the animal kingdom; most people are familiar with a “pack of wolves,” a “herd of cows,” a “school of fish,” a “murder of crows.” Social psychology suggests that we humans are not so different.

As Gustave LeBon writes in his book, “The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind:”

“To pass in pursuit of an ideal from the barbarous to the civilised state, and then, when this ideal has lost its virtue, to decline and die, such is the cycle of the life of a people.”

Contained therein are echoes of Julius Caesar’s Rome, of Elizabethan England, and of the United States of America in the year 2014.

LeBon goes on to say:

“Organised crowds have always played an important part in the life of peoples, but this part has never been of such moment as at present. The substitution of the unconscious action of crowds for the conscious activity of individuals is one of the principal characteristics of the present age.”

The “present age” LeBon speaks of was the year 1895, when his book was published.

Civil unrest and crowd psychology are still with us today. And in the age of the Internet and social media, to borrow from LeBon, this part has never been of such moment as at present. It is my sincere hope that all people impacted by violence, be it here in the U.S. or abroad, can find some comfort and ease very soon. It is my sincere belief as a human being and an artist that in looking to our past, we can find some perspective for the present and some hope for the future.

That’s all for now. Please come and consider these issues with us when Folger Theatre presents Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar this fall.

If this topic is of interest, you can read Daniel Pick’s book here, with free registration through JSTOR, and you can read Gustave LeBon’s book here, for free at Project Gutenberg.

And, as always, you can follow me on Twitter to continue the conversation.

Stay connected

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.