Some close observation and deductive reasoning led commenters in the right direction in solving the June crocodile mystery. Here’s image that I posted last week, with a bit more context:

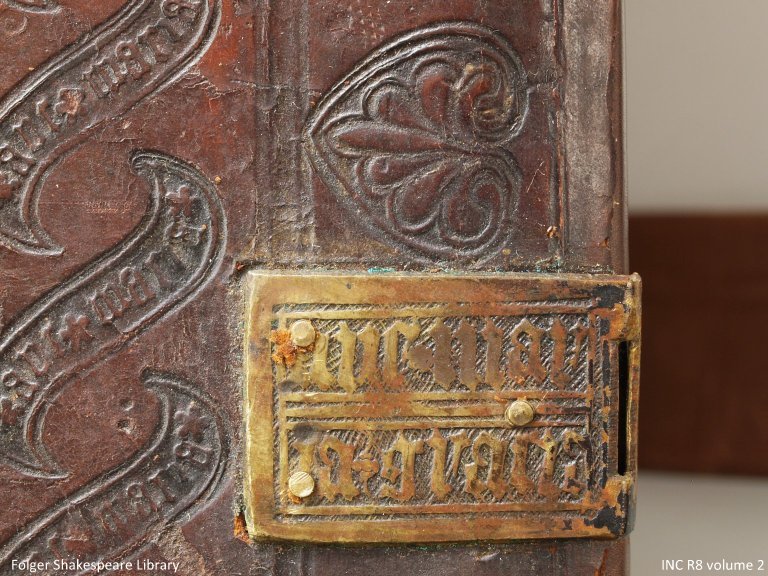

With that bit of the surrounding context, it’s much clearer that it’s a picture of the catch to a clasp on a fifteenth-century calf binding. 1

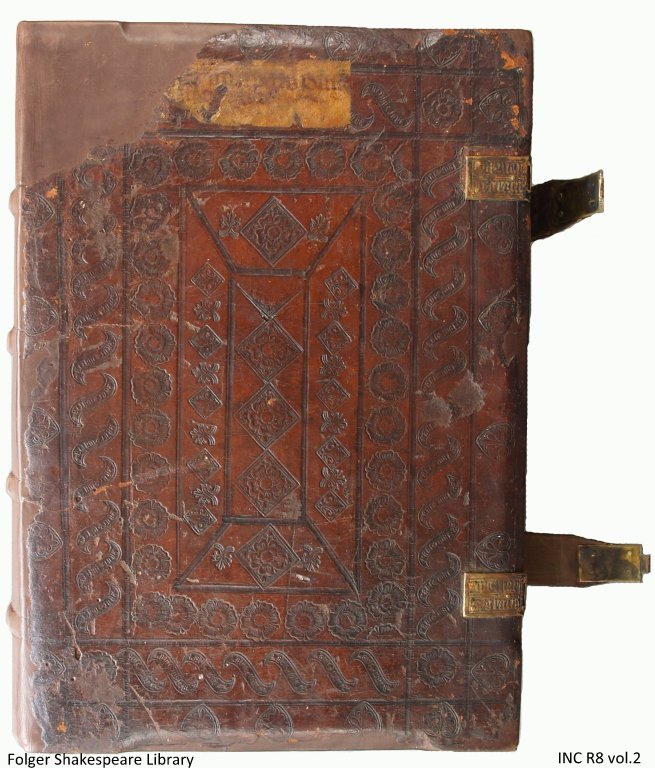

It’s a lovely binding for a work printed in Augsburg in 1474 (Rainerius de Pisis’s Pantheologia, in two volumes) and bound around the same time. Images of the bindings of both volumes can be found in the Folger’s new Bindings Image Collection, including views of the front and back boards and details of the clasps and tooling; the clasp I featured is from the second volume.

I like clasps in general, perhaps because books today don’t generally have clasps, but also because they’re good reminders of the materiality of books: if books were weightless texts, they wouldn’t need clasps to hold them shut! Clasps can range from fairly simply to increasingly decorative:

The clasp featured in this post is especially nice for the way that it is integrated with the binding. As some commenters noted, you can read some text that is part of the catch: “ave maria gratia,” the opening words to the Hail Mary prayer and here split across two lines: “ave·mar / ia·gratia” (the rivets obscure the first letters of each line and, of course, if you’re not used to reading gothic fonts, the letter forms can be a bit mysterious).

INC R8 vol.2 clasp catch

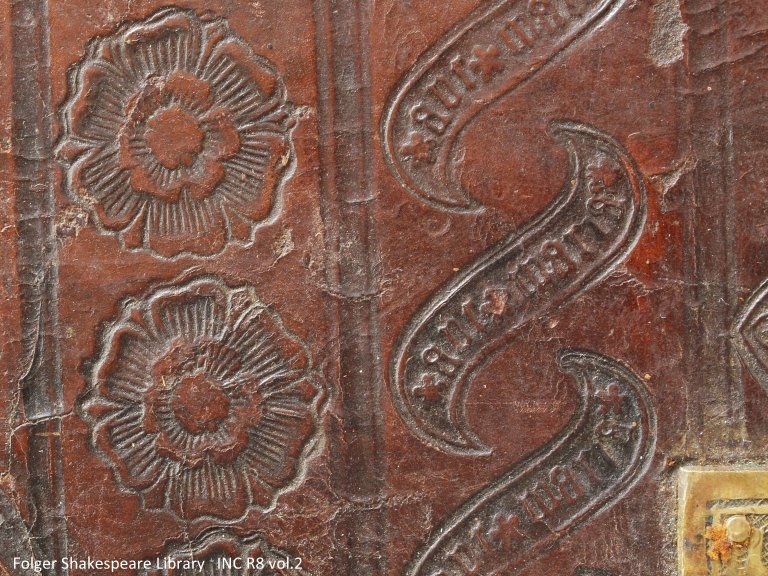

And if you look carefully at the tooling, you’ll see that the scrolls around the border repeat the “ave maria”:

One relevant binding detail that I learned from Frank Mowery, formerly the Head of Conservation at the Folger, currently Rare Bindings Specialist and the man behind the new Bindings Image Collection: clasps on continental bindings have the catch on the upper cover and the hasp on the lower, as in the ones I’ve featured here. But English bindings do the reverse: the catch is on the lower cover and the hasp on the upper. I don’t know why this is, but I do know that it makes reading British-bound clasps harder to work with, since they seem in more danger of catching on the open leaves of the book! (See, for instance, this early seventeenth-century binding, in which the clasp hangs down from the top cover.)

We’ll cover more aspects of the Bindings Image Collection in future posts, but in the meantime, start exploring it on your own. There are lots of detailed pictures of bindings along with descriptions of what you’re looking at. You can search for specific materials, find examples of edge treatments, or browse through different periods or countries. Have fun!

- But of course, the context makes solving the mystery too easy! But the visible details—the rivets holding this in place, the catch opening on the right—were enough to lead observers to its identity. Kudos to John Lancaster, who was the first to suggest that it was the catch-plate to a binding clasp.

Stay connected

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Comments

I love clasps and bindings! Thanks for this informative and delightful post. I’m very excited about the Bindings Image collection.

Miriam Jacobson — June 12, 2012